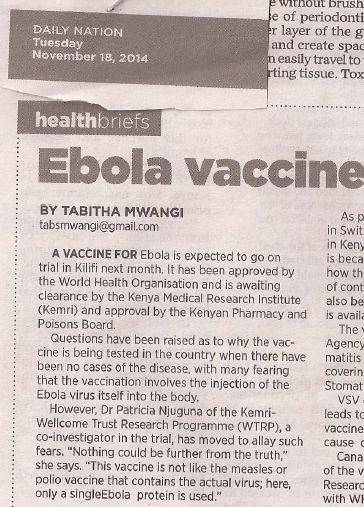

Ebola vaccine trial in Kenya

If you turned to DN2 bit of the Daily Nation newspaper today (18th November 2014), on page 4 just under the article about dental health, there is a little article titled ‘ Ebola vaccines to be tested in Kenya’. I thought I had nailed a really nice topic when I handed this article to the editor. I imagined blazing headlines – clearly, I was deluded – not even a url. My piece of art belonged under ‘bad teeth’…..sigh! Don’t condole with me too much though —– am just kidding! However, have a read of the article and let me know if you thought otherwise…….

A vaccine for Ebola disease will soon be tested in Kenya. The trial has already received approval from the World Health Organization and is awaiting clearance from KEMRI before final approval from the Kenyan Pharmacy and Poisons Board. It is expected that by the beginning of December, participants will start receiving the Ebola vaccine.

It may come as a surprise to many that an Ebola vaccine is being tested in a country where the disease has not been detected. Many are concerned that vaccination involves the injection of the Ebola virus itself into humans.

‘Nothing could be further from the truth,’ says Dr Patricia Njuguna of KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Program (WTRP), who is also a co-investigator on the trial. ‘This Ebola vaccine is not like measles or polio vaccine that contains the actual virus, here, only a single protein of the Ebola vaccine is used,’ said Dr Njuguna.

As part of this trial, a total of 215 people will be vaccinated in Switzerland, 30 in Germany, 60 in Gabon and 40 in Kenya. Almost all the people being vaccinated are health care workers. This is because this is a group of people who have an understanding of how the vaccine works but are also the first line of contact with Ebola patients. Many health care workers have contacted Ebola from patients and passed it on to others. Health workers will also be the primary targets of the vaccine once it is available and therefore form the bulk of the study participants.

The vaccine was made by the Public Health Agency of Canada by combining the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV) with a portion of the protein covering the Ebola virus, hence the name of the vaccine Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Ebola Vaccine (VSV-EBOV).

The Vesicular Stomatitis Virus causes disease in domestic animals and when humans are accidentally infected, they get a mild flu-like illness. For the vaccine, this virus has been weakened and cannot cause disease to animals or humans.

The Public Health Agency of Canada had already started human trials of this vaccine at the Walter Reed Institute of Research in the USA in October 2014 and have partnered with the World Health Organization in order to hasten the process of vaccine development.

The World Health Organization consortium carrying out these trials requested the KEMRI-WTRP in Kilifi, which has a clinical trials facility, to participate in this effort. Researchers on the ground like Dr Njuguna, have been involved in managing large malaria vaccine trials and are familiar with the workings of clinical trials.

‘All 40 of us who will receive this single dose vaccine will be followed up for one year to find out whether we continue to produce antibodies that can protect us against Ebola for a while,’ said Dr Njuguna.

There is another Ebola vaccine, known as ChAd3 ZEBOV (ZEBOV), produced by Glaxo-SmithKline (GSK) that is undergoing human testing. This trial started in early September 2014 with the target of 100 people vaccinated in the USA and Switzerland, 60 in the UK and 80 in Mali. All vaccinations will be complete by end of November and just like the VSV-EBOV vaccinations, this vaccine trial is targeting health workers.

Both VSV-EBOV and ZEBOV vaccine trials are funded by several sponsors including the Wellcome Trust, MRC and the Department for International Development from the UK, the US National Institutes of Health and others working in partnership with through the World Health Organization. It is hoped that testing both simultaneously will increase the chances of identifying a very safe and highly effective vaccine.

Both vaccines are at the phase one stage of clinical trials. This is the period when a vaccine has already been tested on laboratory animals including primates (monkeys or apes) and now needs to move to human beings. At this stage, researchers are keen to look for any safety issues. This is why they are particular to use groups of people that are well informed about the study and will follow the protocol to the letter. This is also the stage where researchers will be able to decide on the dosage of the vaccine that is most effective. The lower the dosage required, the cheaper vaccine production will be.

Phase one studies usually don’t involve more than a few hundred people.

Phase two studies are useful for determining how well the vaccine works or in the case of the Ebola vaccine, whether participants are producing antibodies in quantities that are protective.

Phase three studies are the ones that determine whether a vaccine will be licensed. Several thousand people who are at risk of the disease are vaccinated and compared to non-vaccinated people. For the case of the Ebola vaccine, this phase three trials will be conducted in the Ebola hotspots of West Africa. This is the point when researchers will know for sure that the vaccine is effective, that those volumes of antibodies that the vaccine causes people to produce can actually protect against infection, hence the need for the study to be conducted in Ebola hotspots.

Prof Adrian Hill from Oxford University, is leading the UK study on ZEBOV. I spoke to him during the 25th anniversary celebrations at KEMRI-WTRP in Kilifi and he said that the speed of vaccine development for these vaccines is unprecedented.

‘Never has a phase one trial of a vaccine been started while an outbreak is ongoing with the aim of using the vaccine to stop the epidemic,’ said Prof Hill, ‘However, there are fears that the Ebola virus could mutate and become even more transmissible and we need to very quickly get the vaccine on the ground.’

If the vaccines on phase one trial are found to be safe and data shows that humans can produce large amounts of Ebola antibodies that are protective after vaccination, the plans are to move straight into phase 2 and 3 clinical trials early next year.

‘The way forward is not fully agreed but the likely scenario is that Phase 2and phase 3 trials will start simultaneously in January 2015. Phase 2 clinical trials will likely be conducted in West African countries without cases at the moment. This could include Nigeria, Ghana and maybe Senegal. They will involve 3,000 people and will give a good picture of safety. Phase 3 will be the more difficult one as we will want to give the vaccine both to save lives but also to test the vaccine,’ said Prof Hill.

In ‘normal’ vaccine trials, researchers move from one step to the other in a pre-programmed way. Phase 3 will only start when phase 2 is complete and the vaccine cannot be given to all until phase 3 studies are completed and the vaccine licensed. For Ebola, this would lead to ethical complications.

‘For Phase 3, we will probably start by giving the vaccine to one group and comparing them to a group without the vaccine. Very careful monitoring will be conducted so that when it is obvious that the vaccine group is performing better, then all the people in the study will be vaccinated and the trial stopped,’ said Prof Hill.

The ZEBOV vaccine was manufactured in the UK some time ago but prior to this outbreak, no major pharmaceutical company would invest significantly in vaccine development. After all Ebola occurred mainly in Zaire, a poor country through whom pharmaceutical companies were unlikely to recoup the huge costs required to develop the vaccine. The money to develop such a vaccine needed to come from the public and this has come through efforts by the WHO and from charities like the Wellcome Trust and from governments.

According to the WHO report of 12th November 2014, there have been 14,098 reported cases of Ebola with 5,160 deaths. This should never be allowed to happen again. Once the outbreak subsides, countries within Africa need to plan ahead to avoid serious outbreaks of Ebola in the future. If the health workers who handle the patients and the immediate contacts are quickly vaccinated, then the disease has a low likelihood of spreading.

‘Ebola vaccines need to be stockpiled in countries were the outbreak can happen so that immediately an epidemic begins, the vaccines are used immediately to stop the spread of the disease,’ said Prof Hill.