My mother is a prostitute…… what does that make me?

A Swahili saying goes ‘mtoto wa nyoka ni nyoka’ – that the child of a snake is a snake. This little saying is often always used when referring to a negative trait present in a parent. So what do you imagine is the outcome of the life of a little girl raised by a single mother who is a commercial sex worker?

In 2013, I interviewed such a girl. I could not get the story published in main stream media and I held on to it for a long time – don’t ask what magic I was waiting for! There is really no reason to hold on to this story anymore.

I named this girl Sally to protect her identity. Read Sally’s story as she told it back then – and re-think your attitude about ‘that woman’s children’.

Sally is tall and slender with an even dark complexion, soft spoken and appears averse to drawing attention to herself. For the 21 year old, her focus is squarely on her future.

‘When I look back and see where I have come from, I know that I will go very far in life. There are not many girls in my situation who have come this far,’ Sally says with a smile.

Sally was raised by her mother, who was and still is a barmaid and commercial sex worker (CSW) in the slum of Barsheba, Mombasa. She has no idea who her father is.

Sally lived a relatively secure life with her maternal grandparents in Migori, before they both passed away when she was five years old. After the funeral, Sally’s mother had no choice but to take all her children back with her to Mombasa. Sally and her elder brother found themselves in a single room, with a smaller sister they did not know and a man they had to call ‘baba’.

‘My mother was very abusive towards me and kept telling me that ‘you girls are not going to help me, you are going to be Malaya (prostitute). Only the boy will help me,’ Sally said, pointing to two scars on her chin and forehead, a reminder of the days when she was her mother’s punching bag.

While her brother went to school, Sally stayed at home, taking care of her little sister. As there was a nursery school near the home, she would play with the children during their breaks. With time, the nursery school teacher let Sally stay in the class and later managed to convince her mother to pay the school fees. In 2003, when she was in Standard 4, President Kibaki introduced free education and Sally was able to study without fear of being thrown out of school. But there were a few changes at home.

‘My mother had a new man in the house called Jack*. They fought almost on a daily basis, often because Jack had found my mother with other men. It was difficult to study with those two throwing everything all over the house. It was also so embarrassing,’ Sally said

The couple’s fights were so frequent that the neighbours did not bother to stop them even when Sally’s mother called for help. Sally’s elder brother was unable to cope with the stress at home and ran away to live with his friends who worked odd jobs on the streets of Mombasa. He never completed primary school and Sally has no idea what her big brother is doing or whether he is alive.

Sally’s mother conducted her sex work at the bar but sometimes, men would come to her home and take her away. Sally and her sister referred to these men as ‘baba mkate’. Sometimes, when they were short of food, Sally’s mother would ask her to call one of the ‘baba mkate’.

‘It was awkward. My mother would dial the number and hand her mobile phone to me, directing me on what to say. ‘Shikamoo, we have not eaten today and I don’t have fare to go to school,’ was what I often said. When I was younger, I used to wonder to myself about this person that I was calling, why is he helping? Who is he? But that was before I understood, that these, were all my mother’s clients,’ Sally said.

Except Jack, none of other clients slept in their one-roomed home. Jack once attempted to sexually molest Sally, then a Standard 7 pupil, but failed. The attempt left Sally feeling so violated, she walked alone to the Bamburi police station and reported the matter. When she told her mother about her visit to the police station, her mother gave her a thorough beating and she was not allowed to pursue the case any further. Although Jack ceased to sleep in the house, he still has an on-going affair with Sally’s mother to date.

Her mother’s reputation made life difficult for Sally.

‘My friends would tell me ‘You can’t walk home with me, my mother has said she does not want to see me with you, I don’t want problems’. Sometimes my sister and I would be referred to as ‘watoto wa yule mlevi’ (children of that drunkard). Even at Sunday school, the teachers would by-pass my raised hand and tell me ‘you can tell us later’, if I wanted to answer a question. They felt I had nothing of use to say,’ Sally said.

For Sally, the fact that people expected little from her spurred her to perform as best as she could. At the end of her primary school, Sally scored 289 points but spend the month of January at home for lack of school fees. A lady teacher who frequented the bar her mother worked in, organised a harambee which raised enough money for Sally to join a day government secondary school in Mombasa. After failing to pay 3 school term fees, Sally was about to drop out of school when her deputy head-teacher asked her to visit the Solidarity with Girls in Distress (SOLGIDI) offices.

http://www.maryknollafrica.org/mombasa/solgidi.htm

Agnes Mailu, the head of SOLGIDI program, visited Sally’s home to confirm her story and they decided to sponsor her schooling.

‘We target children of CSWs from slum regions of Mombasa. Women who will sell their body for as little as 20 shillings. For some of these women, making 100 shillings a day is a lot of money. The relationships between such women and their children is often very bad. Exposure to a good education will give a child of a commercial sex worker the chance that her mother never had to see that there are other opportunities to make a living. These children did not choose to be born by a prostitute and none of them want to be their mother. Those we are able to help, like Sally, are appreciative,’ said Mrs Mailu.

The sponsorship does not cover lunch and fare to school, Sally’s mother is expected to take on some responsibilities for her child. But because of the difficulty she faced, Sally’s geography teacher offered to pay her lunch, giving her KSH 500 every week. But those were not the only problems for Sally.

Their house in the Barsheba slums has no electricity and sometimes there was no money for fuel to light the lamp.

‘I remember once trying to finish my homework by sitting at the back of a neighbour’s house. When the woman of the house realised that I was reading using the light streaming from her house, she went into her house and switched of the light, saying that I was being a show-off with all that reading,’ said Sally.

Her monthly periods were another time of distress and her mother would snap at her with irritation ‘do I buy unga for food or your pads?’, she would ask. Sally was forced to make do with pieces of cloth.

‘At such moments, some men would approach me, telling me that they would give me 1,000 shillings if I slept with them. I would imagine buying pads with that money but I would resist,’ Sally said. She stops talking for a moment and shakes her head, ‘I just don’t know how I got this far without falling into temptation,’ she says.

Sally scored a C+ for her KCSE but that meant she did not qualify for a government bursary. She was also getting desperate to leave home.

‘It was not just my mother’s drinking but the conditions at home. Even upto now, I sleep on the floor with my sister, the bedbugs make sure that we don’t get enough sleep. The toilets are awful to use. I just wanted to sleep in a nice place,’

She attempted training as a nun but soon realised that it was not a profession to be undertaken due to need but from an inner calling, so she abandoned it. Finally, she took on a job as a house maid in Tudor, earning KSH3,000 a month. It was during this time that her plight was highlighted by one of her old teachers and she was contacted by SOLGIDI staff. She was able to enrol for a degree program at Mt Kenya University. Sally is now a second year student at the Mt Kenya University in Mombasa.

‘I was concerned that if she did not enrol to college, she might end up on the street. This is a problem we face with our students. Last year, 11 of our girls scored B- and above. Parallel degree programs are expensive, but the alternative, of watching these girls live their mother’s life, is worse,’ said Mrs Mailu.

‘Money is still a problem so I plait hair and wash people’s clothes to get fare and lunch money. But on top of school fees, SOLGIDI had made me feel that I am capable of doing something with my life,’ said Sally.

SOLGIDI offers training days to all sponsored children, all of whom are children of commercial sex workers. They share life experiences and are offered counselling. They also have a strong mentorship program. University students mentoring secondary students and secondary students mentoring primary students.

‘My mentor has just earned a scholarship to do her Masters degree in the United Kingdom. She has been such an encouragement. The girl I mentor is in a boarding secondary school and I go to the school during visiting day because her parents are not able. I buy a few things for her shopping with the little money I have. It’s not just school fees those of us in this circumstances need, but encouragement,’ said Sally.

Sally’s mother currently earns KSH 4,000 from her work as a bar maid. She has to pay secondary school fees for her youngest daughter, pay rent and feed the family. She has no other business and so sex work continues to supplement her income.

‘There was a time I would not be able to talk like this about my life. I was so ashamed of it. But SOLGIDI has brought me far. That was the life I lived, I am not there anymore. I am headed somewhere,’ said Sally, with that quiet confidence.

But there are more children in need than SOLGIDI can cope with and the expenses of taking children through high school are immense.

‘I will give you an example, we have a girl who was admitted to a national school. The school fee was 65,000 shillings. She applied for CDF support and got 10,000 shillings. Where will a CSW get the remaining 55,000 shillings from?’ asks Mrs Mailu.

But even those children in primary school suffer as a result of community neglect.

‘We need safety nets in this country. If a child does not go to school, someone should be responsible to ensure they get to school, whether the child is rich or poor. Whether the mother is a CSW or not,’ said Mrs Mailu.

************************

A SHORT HISTORY OF SOLGIDI

Solidarity with Girls in Distress (SOLGIDI) was set up as an offshoot of Solidarity for Women in Distress (SOLWODI).

http://www.solwodi.de/197.0.html

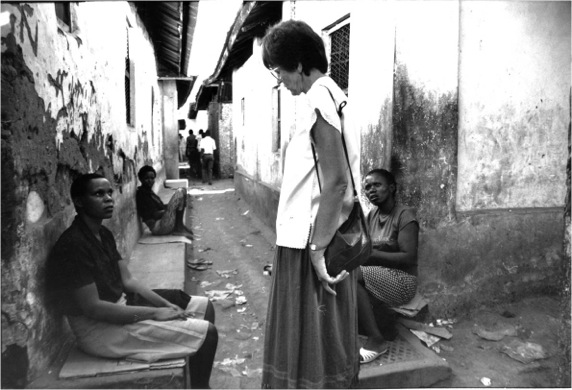

SOLWODI was started in 1985 by a Roman Catholic nun, Sister Lea Ackermann in an attempt to give women and especially young girls in Mombasa, who were involved in prostitution, an alternative life.

It was also not lost to SOLWODI that despite rescuing many commercial sex workers (CSWs), there were ever more young women joining the trade, many who were children of women practising prostitution.

‘One young girl told me how frightened she was at night as her mother would dress up and leave her alone in the house with her little brother. Other girls had to leave the single-roomed houses, when ‘clients’ came to see their mother. The little children were alone in the streets in the dead of the night. In other situations the ‘clients’ got drunk and would even touch the children. That was when with Agnes Mailu, we create a new organization for daughters of women working in prostitution and SOLGIDI was born in 2002,’ said Sister Lea.

Since its inception, SOLGIDI has rescued about 140 girls each year. Sister Lea who is now 78 years of age, lives in Germany, where she raises funds for the organizations she had set up.

As she is aging, sister Lea is concerned about continued assistance for these children and urges more Kenyans to be involved in supporting them for the simple reasons that she does.

‘For me as a Christian all people are created by God, we all are his children. But some of his children live in conditions offering not the slightest chance for them. I am convinced that those children of God, who live in better conditions, who have more luck in life, should help those who don’t get these chances. As a nun, in the discipleship of Christ, I feel I am obliged to do that. God does not have any other hands but ours!’ said Sister Lea.

**************************

My mother is a prostitute…… what does that make me?

We can all help SOLGIDI mirror to our girls the alternatives open to them.

Comment

Comments are closed.

SOLWODI

Thank you so much for your moving article on the situation in Kenya and our work there! It is so important to give these children the chance to live a better life, to get education, to feed themselves – especially girls.

It might be a big help if organizations pay school fees or teach girl income generating skills. But it will be of incomparable value, if these children experience appreciation from society. They are the weakest part and need our help!