Dilemma of separating conjoined twins

Those who followed the story of the conjoined twins of Nakuru may have wondered why no efforts were made to separate them, to at least save one. However, separating conjoined twins is not always a straightforward issue and the dilemma faced when making a separation decision is older than you may have imagined.

The first attempt was made in AD970 in Armenia. A set of conjoined male twins had lived, joined together at the hip, for 30 years when one passed away. Surgeons decided to separate the dead twin in order to save the living one, unfortunately, he died within 3 days of the surgery.

In AD1100 34-year old conjoined twins Mary and Eliza, popularly known as the ‘Biddenden maids’, suffered an almost similar fate. They were joined at the head and shoulder and when Mary fell ill and died, Eliza refused to be separated from her sister and died 6 hours later.

A paper titled ‘Conjoined twins’ published in 2003 by Prof Lewis Spitz of the Great Ormond Hospital in the UK, examined published work on 167 separated conjoined twins. All the data put together showed that half of those who shared a heart died at separation with the lowest mortality of 1 in 5 among those joined at the hip.

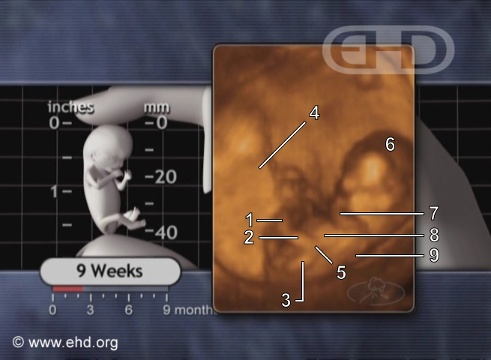

In the developed world, conjoined twins are detected in the first trimester of pregnancy during routine ultrasound scans. Terminations are recommended for those conjoined twins that share a heart or brain as survival post birth for such a pair is minimal. Many parents opt to terminate most cases of conjoined twins as soon as they find out.

Congenital twins are most often than not delivered by caeserian section and action at that point will depend on the seriousness of the cases. In cases were it is not possible for the children to be separated and live, for example if the two share a heart, no surgical intervention is undertaken, and such conjoined twins die. This appears to have been the case for the twins born to Evelyn at Nakuru Anexx hospital.

An emergency separation is performed when one twin is born dead or threatening the survival of the other. Eight of such 10 emergency operations end in death for both babies. The most favourable route is delayed separation at 2-4 months as it allows the twins to stabilize and gives doctors time to make thorough investigations. There is an 80 percent survival rate for such cases where best medical care is available. Some researchers have reported better outcomes when surgery is delayed by upto 10 months.

However, there are moral issues when it comes to separation of twins.

There is no better example of this, than the public legal battle in 2000 regarding the separation of conjoined twins given the false names Mary and Jodie to protect their identity. They were born in St Mary’s Hospital in Manchester by a Meditteraenan couple who came to the UK to deliver, once they realised that they had conjoined twins.

Mary and Jodie were joined at the abdomen with fused spinal cords, arms and legs at right angles to their body. Jodie, the stronger twin had a normal brain, heart, lung and liver but shared a bladder with her sister.

The doctors believed that the twins should be separated as left together, both would die within 3-6 months. However, if they were separated, Mary would die while Jodie would survive. Jodies’s heart and lungs were keeping Mary alive. Mary was described as ‘draining the life out of Jodie’. The parents were opposed to Mary being ‘sacrificed’ for Jodie. The wanted nature to take its course- God’s will to prevail.

The case was moved to the family division of the High court. The English law forbids the taking of an innocent life for the benefit of another. In the end, necessity ruled the day. The children who were born on 8th August waited until 7th November for the 20 hour operation to separate them to be performed. Mary passed away as was expected but Jodie did well after surgery and is probably living a normal life with her parents in Malta.