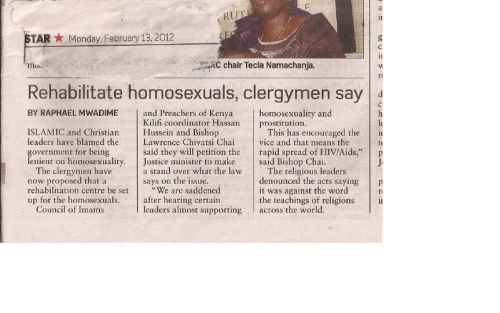

On ‘treating’ homosexuality

I saw this tiny article in ‘The star’ last year and it got me thinking – do people actually attempt to ‘treat’ homosexuality? The answer is yes. However, the ‘treatments’ have undergone dramatic changes over the years.

Although it may sound like a backward call by the religious leaders, it is the same route that was taken in the UK: criminalising homosexuality, trying to treat it and then accepting it. It is worth noting that despite the noise around the world at the moment on gay rights, it was not until 1992, just 20 years ago, that homosexuality was removed from the WHO International classification of diseases.

I will take you through a short history of ‘treatments’ applied to treat homosexuals – my blogs are more of articles really than blogs but bear with me, this is an interesting one. As usual, I focus on peer-reviewed published information, which is heavily biased to the UK and US experience.

The beginning

Since the development of sexology (the science of sex and sexual relations) in the late 1800’s and a century after, medicine uniformly defined socially unacceptable sexual behaviours, such as homosexuality, as a mental disorder or illness. Interventions were developed in line with what at that moment was thought to be the cause of the homosexuality.

Homosexuals underwent interventions that involved castration as well as inducing convulsions through electric shocks to disrupt unwanted brain activity. Prefrontal lobotomies that were used to ‘treat’ cases of schizophrenia and hereditary defects were also conducted on homosexuals. This involved drilling holes in the skull and using a blade to cut of nerves connecting the front part of the brain to the rest of the brain. It was believed that psychiatric symptoms or in this case, homosexuality, was as a result of faulty ‘wiring’ and if these were cut, allowing for new connections to form, the new ‘re-wiring’ would cure the patient.

From 1950’s

In America and Europe, after World War II, legal sanctions against homosexual behaviour peaked and this was the foundation for interest in psychological interventions to alter sexuality – which increased sharply in 1960-70’s. Homosexuality was still considered an illness but it had been criminalised. In the UK, clinics for treating homosexuals were set up in London, Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow and Belfast. Homosexual men were referred from courts and the option was jail for their homosexual lifestyle or face treatment – the same thing that the religious leaders on the coast were suggesting last year.

So what did they do to these men at the clinics?

Treatments were based on the belief that homosexuality was a learned behaviour, which could be unlearned through providing skills to generate heterosexual arousal and improve skills with the opposite sex. Treatments involved sexual re-direction through psychoanalysis or aversion therapy.

The most common mode treatment upto the 70’s was behavioural aversion therapy and oestrogen treatments to reduce libido. Aversion treatments aimed at re-directing sexual arousal to the opposite sex by punishing homosexual desires using electric shocks, nausea inducing drugs or threats of violence. Other treatments included; discussions of the evils of homosexuality, desensitisation of an assumed phobia of the opposite sex, hypnosis, psychodrama, dating skills and encouragements to attempt heterosexual sex.

The Wellcome Trust funded research looking at oral histories of patients who had undergone mainly aversion therapy treatment for their homosexuality in the United Kingdom from 1950’s and professionals who treated them. The work conducted from 2001-2004 interviewed 31 former male patients and 30 professionals who were involved in their treatment. The studies are published in the British Medical Journal that can be downloaded free on-line.

Wellcome Trust research on treatments for homosexuals

In electric shock therapy, electrodes were attached to the wrist or lower leg and shocks administered while the patient watched photographs of men and women in various stages of undress. Shocks were administered when same-sex photos were shown. It was hoped that arousal to same sex photographs would reduce while relief arising from shock avoidance would increase interest in opposite sex images. The therapist would be in the room, behind the screen administering shocks when same-sex photos came up. Treatments lasted 30 minutes.

Electric shock therapy was preferred to apomorphine treatment though the same principal applied. Viewing same-sex photos was accompanied by administration of the nausea-inducing drug (apomorphine) which was hoped would lead to aversion for same-sex sexual persons. However, apomorphine treatments often required that a patient be admitted to hospital due to the side effects of the drug. In the course of this line of treatment, a patient passed away.

Life after treatment

For many, the desire to fit into the heterosexual lifestyle was strong and 7 married. Six divorced due to ‘sexual incompatibility’ and one stayed in a sex-less marriage. Twenty-four remained single, 3 men never had a sexual life due to the treatments they went through. Those treatments made them totally asexual, unable to be aroused by either men or women.

Apart from these participants in the Wellcome Trust study, there is the now very famous story from England of Alan Turing, now revered as the Father of computer science. Alan was arrested for homosexuality in 1952 and to avoid prison subjected himself to chemical castration using oestrogen injections for a year. Unable to cope with the persecution, he committed suicide in 1954, aged 41.

In conclusion – the treatments were not effective in changing sexual orientation. The authors of the papers believe that medicalizing homosexuality was more the problem than the treatment themselves. In the UK, same-sex sexual acts were descriminalised in 1967.

But treatment continues.

Currently, the primary sexual conversion organization is known as The National Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH) in the USA. NARTH believes that if content homosexuals are accepted, discontent homosexuals who pursue change should be equally accepted and given a chance to change their sexual orientation.

The current thoughts of those that pursue sexual orientation conversion are that, homosexuality is a condition or ‘addiction’ that results from a boy not receiving sufficient love or role modelling from their father. This is supported by Dr Tony Bieber’s work in the 1970’s who after interviewing 1,000 homosexuals said, ‘I have never interviewed a single homosexual who had a constructive loving father.’ This apparent void caused by a lack of connection with the father causes the boy-child to sexualize same-sex emotional needs. This theory pre-supposes that all men are baseline heterosexual, and that latent heterosexuality can be encouraged in the homosexual through ‘brain-training’. Treatments engage various forms of psychotherapy.

A paper published by Professor Robert Spitzer in 2003 stating that aversive conditioning and spiritual intervention could change sexual orientation, boosted NARTH’s cause greatly.

Roberts paper claiming some people can change sexual orientation

Prof Spitzer had interviewed 200 self-selected individuals who claimed to have been cured of their homosexuality. However, last year (2012), Prof Spitzer retracted the paper claiming it was impossible to tell whether his interviewers had genuinely changed orientation. ‘I believe I owe the gay community an apology for my study making unproven claims of the efficacy of reparative therapy,’ he is quoted by the New Scientist, May 26, 2012, to have said.

Due to the conflicting information by groups pro and against sexual orientation change, the American Psychological Association set up a task force in 2007 to review and evaluate all the studies on sexual orientation change efforts. The task force identified 75 such studies from 1960 to 1985, and concluded that the evidence was not sufficient to support the sexual orientation change claims.

Dr Lee Beckstead, who researches on this field, was a member of the task force. I got in touch with him by email and these were his comments from reviewing the data.

‘The only results we can say that have any empirical rigor suggest that some, but not all individuals who experience aversive treatments do report reduced homosexual arousal but also reduced sexual arousal. That is, they do not become more heterosexual, just asexual, which may seem like a desired outcome. However, my qualitative studies again can provide important information here because my research participants related that they found ways to lie to themselves and others about changes to their sexual orientation. We do not know if these quantitative results are valid because participants’ self-reports may be overly skewed due to their need to misrepresent their results and lie about their reduced arousal for the sake of stopping the aversive treatments and to feel like they are improving, or how long these results last. We do know, and my qualitative results demonstrate, that people can suppress their attractions for a while, especially out of fear, but they do not “go away” but can eventually return through addictive, out-of-control behaviors. Aversive treatments seem to work for some in the short-term but then have more problems in the long-term. The solution is actually the problem. As mentioned in my latest article, attempts to control sexual arousal may actually produce the opposite desired effects. The spread of AIDS may actually be caused in part by same-sex attracted individuals feeling ashamed and fearful about their attractions and not having healthy ways of acting on these attractions but through unsafe sexual behaviors. This is why gay-affirmative interventions are needed to increase the self-esteem, self-acceptance, and healthy sexual behaviours,’ said Dr Beckstead.

I choose to conclude with a comment from Dr Beckstead who has spend a lot of time studying this field and currently focuses his work on providing therapy for those who are in distress with their sexual orientation.

‘The most effective approach is in people evaluating their fears and beliefs about homosexuality and finding ways to reduce the misunderstanding, discrimination, and hostility that exists within sexual minorities and their social situations.

As one of my research participant expressed, ‘I feel that more good could be done by the psychological and religious communities if they were to band together and help sexual minorities shed their self-hatred and find a respected place in society’